Over the last few days, I have been asked repeatedly and by many different kinds of people in many different settings why baseball doesn’t have a salary cap like the other American team sports do. It is right that people ask me. Having studied at Harvard with a concentration in Monetary and Fiscal Policy and then picking up my PhD at the Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics at the University of Chicago, I modestly feel like I can offer deep insight into this question.

Why doesn’t baseball have a salary cap like the other sports do?

Answer: I think it maybe union not like salary cap idea?

But as sound and grammatically correct as this answer is, I’ve started to wonder a little bit about it. That is to say I’ve started to think about the players’ determined and dogged multi-decade battle to fight off all of the salary cap dragons that have consumed other sports … and whether or not they actually won that war.

We’re going into the rabbit hole, folks, so the question now is whether we should start in 1996 … or 1889. Well, what the heck, hopefully you’re in a comfortable chair: American sports first salary cap came in 1889 when the National League literally capped individual salaries at $2,500 (about $77,000 in 2022 money). It was a whole system created by a Civil War veteran named John Brush where players would be graded from A to E based on their play, their character, etc. An “A” player would get the highest salary which was, as mentioned, $2,500.

The players were so enraged by this that they formed their own league, the Players League of 1890. And it did include many star players such as Dan Brouthers, Harry Stovey, King Kelly, Old Hoss Radbourn, John Ward, Jim O’Rourke and others. But even though the league did fairly well at the gate, it was a financial disaster and lasted only one year. All the star players had to go crawling back to the National League.

That doesn’t really have anything to do with our story, but it does tell you just how long baseball players have been fighting against salary caps.

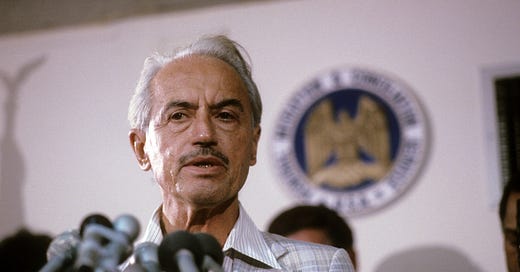

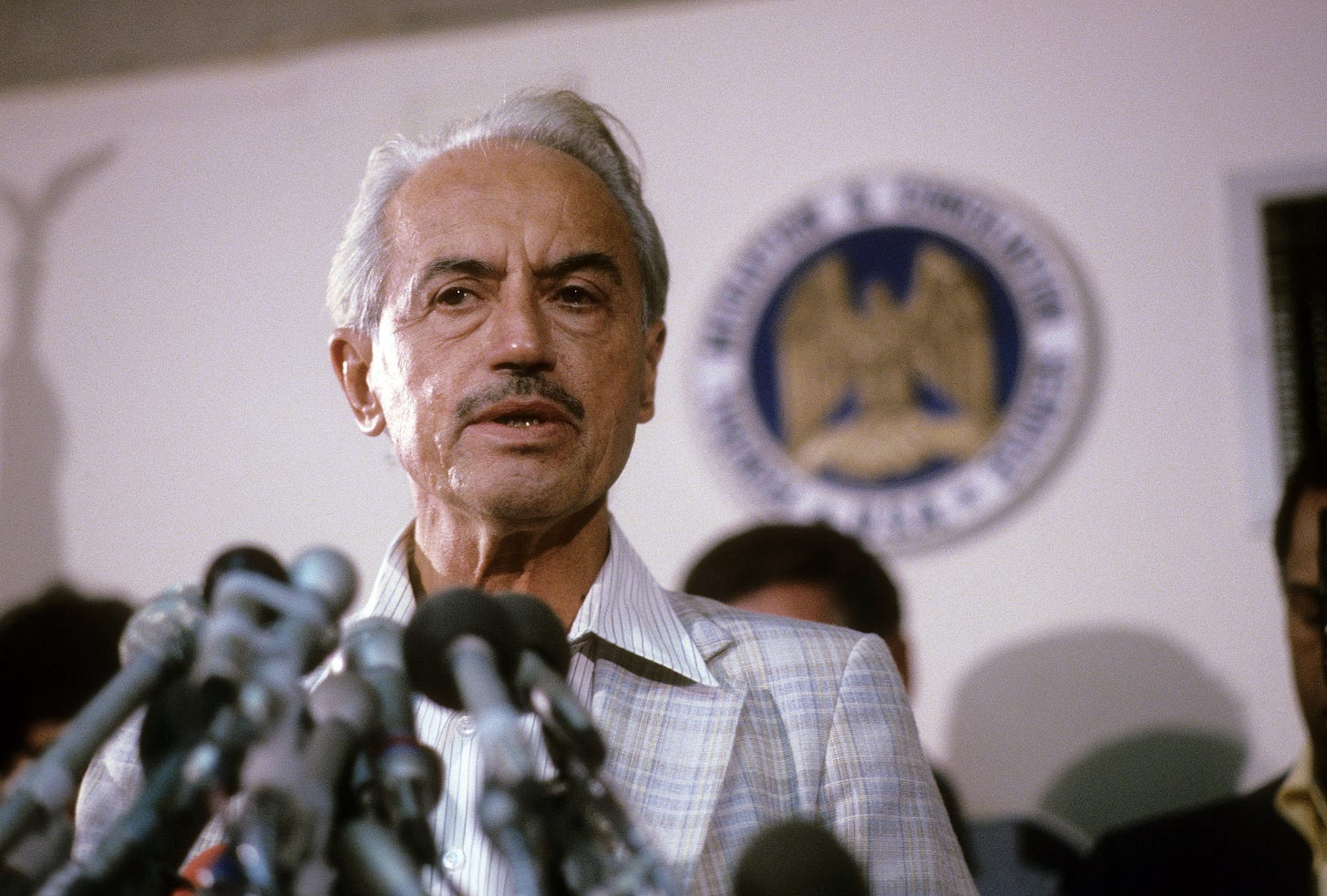

OK, let’s move ahead more than 100 years. By this point, the owners had tried many different times to enforce or finagle a salary cap but the players had rebuffed them at every turn. Union head Marvin Miller was, I think he’d be proud to say, a zealot for the players, but he was a particular zealot on this subject — in his mind there could not be any mechanism to limit what players could earn. He utterly loathed the NBA salary cap and took every opportunity to say so.

To Marvin Miller, it didn’t matter if the salary cap was a billion dollars. His unmovable viewpoint was this: No limits. End. Of. Conversation.

“The owners want to set salary levels below the market value,” he used to say. “That is the reason — and the ONLY reason — for all salary caps.”

In 1994, the owners decided to go to the wall for a salary cap. Their idea was essentially like in football and basketball — they would tie salaries to revenue, and they would set the cap so that 50% of the revenue went to the players. The owners wanted the players to counter with a higher percentage, even it was a MUCH higher percentage, but it goes without saying that the players wouldn’t even negotiate if a salary cap was involved.

There’s a particularly poignant scene in the classic “Lords of the Realm,” where one of the owners’ lawyers approached my friend Steve Fehr (a union lawyer and brother of union head Don Fehr) at the All-Star Game and basically shouted at him, “Give us a number! Give us a number! Give us a number!”

That owners’ lawyer’s name: Rob Manfred.*

*Steve Fehr compares this with the famous Winston Churchill joke — anyway, it’s usually attributed to Churchill though he almost certainly said it. Churchill is at a party, drunk, and approaches a woman and asks if she will sleep with him for $100,000. She says she would. He then offers a dollar, and she slaps his face saying, “What kind of woman do you think I am?” He replies, “We’ve already established that, now we are haggling over price.”

Well, you know what happened in 1994 and 1995 — canceled World Series, horrifying replacement player scheme, Congressional hearings, worst moment for baseball since, I don’t know, the 1919 Black Sox? By late 1996, baseball’s landscape looked like a Mad Max movie. And there still wasn’t a deal. And even after the basics of a deal were finally worked out in November, the owners could not get the three-fourths total necessary to ratify it.

Do you know who saved the day? You wouldn’t believe it: Albert Belle.