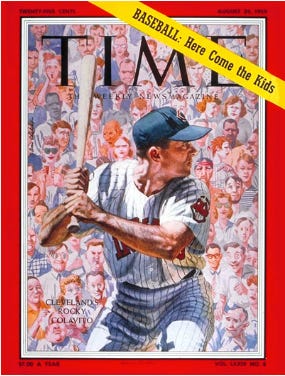

When I was 10 years old—that most magical time for baseball fans—I saw a 44-year-old baseball coach (he looked so much older to me then) stand at home plate at Cleveland Municipal Stadium and throw a baseball over the centerfield wall. It remains to this day the closest I’ve come to actually seeing Superman fly or Spiderman climb or Bugs Bunny defy the laws of gravity (because he never studied law). The throw was a feat so mind-boggling, so utterly impossible, that for years I would actually dream about it, only in the dreams I was that coach at home plate, and I would throw the ball, and it would never come down.

The coach was Rocky Colavito.

I never saw Colavito play—he was traded away from Cleveland for the second time when I was six months old—but I also have no memory of a time when he wasn’t enormous in my imagination. The recurring theme of my Cleveland childhood was that I had arrived at the party too late, that I had missed all the good stuff, I had missed Jim Brown running through defenders, and I had missed Bob Feller and Sudden Sam McDowell throwing fastballs at the speed of sound, and I had missed Lou the Toe Groza booting the football when successful field goals felt like something of a magic trick.

“Aw,” adults would tell me, “you shoulda seen the Rock play.”

He came of age just as Cleveland baseball began to recede. For a time in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Indians served as the minor rival to Stengel’s inevitable Yankees. The Tribe finished second to the Bombers four times but also managed to steal a couple pennants, most gloriously in 1954, when they won 111 games and ran away from the only one of Casey’s teams to win 100 games.

The next year, Rocky Colavito arrived. He had grown up in the Bronx—son of an ice truck driver—who grew up both idolizing and imitating Joe DiMaggio. And while he lacked DiMaggio’s grace (flat feet, alas), he had thunder in his bat and a throwing arm so strong it left the mind reeling. At 16, he dropped out of high school to play ball. He would spend the rest of his life telling kids not to follow in his footsteps.

The Rock had his first great season in 1958. He hit .300 with 41 home runs and a league-leading .620 slugging percentage. He might have won the MVP award, but this was just after Cleveland’s legendary pitching staff—Feller! Lemon! Wynn! Score! Garcia!—had turned to dust, and Cleveland finished a distant fourth, and the voters instead gave it to Jackie Jensen, who led the league in RBIs. A year later, Colavito led the AL with 42 home runs, but Cleveland finished second in the league to the surprising White Sox, and three Chicago players finished atop the MVP balloting.

No matter, they loved the Rock in Cleveland. There were countless Rocky Colavito fan clubs. People would chant “Don’t knock the Rock!” at ball games. He had movie-star looks, and he played the game with panache and enthusiasm; he loved coming to the plate with runners on base, and he especially loved showing off that golden arm. Colavito probably airmailed more cutoff men than anyone in baseball history—maybe Vladimir Guerrero later matched him—his most famous airmailing coming in a 1958 game against the Yankees. In that one, he did not only throw the ball over the cutoff man, he threw it way over the catcher’s head, too. Mickey Mantle was at third base at the time, and he headed home—only to see the ball bounce off the grandstand and kick all the way back into the glove of pitcher Cal McLish, who tossed it to catcher Russ Nixon, who tagged out the Mick.

Yes, they loved the Rock in Cleveland.

And then, on April 17, 1960, Cleveland general manager Frank Lane traded the home run champion to Detroit for 29-year-old batting champion Harvey Kuenn. That’s how the massive trade was viewed across America—home run champion for batting champion—and Lane made his views clear.

“The home run is overrated,” he said. “I hated to let Rocky go, but I think our chances of winning the pennant are greater with a steady hitter like Kuenn in the lineup.”

Cleveland would not win a pennant for the next 35 years—heck, Terry Pluto got a whole “Curse of Rocky Colavito” book out of that trade—but in Cleveland, it was about more than curses. It was about Lane soullessly trading away a piece of the city’s heart. Phone lines at The Cleveland Plain Dealer lit up, as heartbroken fans poured out their emotions.

“My teeth almost fell out,” South Euclid’s Marvin Jones said.

“I’ll never go to the ballpark again,” Robert Intorocio on 165th Street said.

“Tie Lane to a boxcar and run him out of Cleveland,” 88th Street’s William Scott suggested.

“The most stupid thing I ever heard,” Beachwood’s David Magner said.

“I belong to one of the Rocky Colavito fan clubs,” eighth grader Carol Kickel said, “It’s all over. We’re going to start a new one, the Lane Haters.”

Nine months later—after Cleveland’s worst season since World War II—Lane traded Harvey Kuenn to the Giants for pitcher Johnny Antonelli and outfielder Willie Kirkland. “As much as I hated letting Kuenn go,” Lane said, without any apparent irony, “I felt this trade would help us because it gives us a starting pitcher and an outfielder who hits with power.”

In his four Detroit years, Colavito averaged 36 home runs and 108 RBIs per season. In those same four years, Cleveland never had a winning record and sank to the bottom in league attendance.

Cleveland’s legendary sports editor Gordon Cobbledick wrote it this way:

“What Lane overlooked was that, incomplete or not, Rocco Domenico Colavito was our boy, and we loved him. Oh, we often got mad at him for one thing or another, but since when has there been a law against getting mad at those we love? We had raised him, you might say, from a pup. He was ours.

“And then, suddenly, because a man named Lane was in the front office, he was no longer ours.”

Colavito was traded back to Cleveland in 1965—after a year in Kansas City—and even at 31 he had enough left to play all 162 games and lead the league in RBIs. The next year, he hit 30 home runs for the last time. He’s one of a few dozen baseball stars who would be in the Hall of Fame if he had managed even a couple good seasons in his mid-to-late 30s. Alas, the Rock was spent.

Cleveland traded him for a second time, in July 1967, this time to the White Sox. It was front-page news in Cleveland, but it didn’t come with the same shock. “No,” the Rock said, “I certainly can’t say I’m surprised.” He played his last big-league game—for his hometown Yankees at Fenway Park, no less—a little more than a year later. Jim Lonborg struck him out in his final at-bat.

Colavito came back to Cleveland as a coach for a time, and I so vividly remember the reverence that surrounded him. When he stood at home plate that day and threw the ball over the centerfield wall—something he would do fairly often, I’m told—I can remember a complete stranger putting his hand on my shoulder and saying something like, “That’s Rocky Colavito! It has never been the same since he was traded.”

He later became a coach in Kansas City—Colavito was actually thrown out of the Pine Tar Game for arguing about George Brett’s bat—and then he returned to his wife’s hometown of Bernville, Pa., to help run his father-in-law’s mushroom farm. “Hard work,” he said. “Real labor.”

The Rock died on Tuesday at his home in Bernville. He was 91 years old. Not long before his death, he was asked how he felt about being the name assigned to Cleveland’s long drought—it has now been 76 years since Cleveland won a World Series.

“I didn’t put any curse on Cleveland,” he said. “I didn’t want them to lose.”

For 32 years, Colavito was the answer to the trivia question "Who was the last position player to be credited as the winning pitcher in a major league game?" He did it for the Yankees in 1968.

Nobody else did it until Brent Mayne for the Rockies in 2000.

I'm old enough to remember when my Detroit Tigers gad the Big 3: Kaline, Cash and Colavito. And my first exposure to fine sportswriting was when a scribe set the scene when Rocky came to the plate, laid his bat across his shoulders behind his neck and flexed his arms: "Pitchers cringe and women sigh."