My Choice for Greatest Living Ballplayer…

Sure, I probably overthought it… but I love my final choice for GLB.

It’s Barry Bonds, right? It’s got to be Barry Bonds. Within a few minutes of Willie Mays’ passing on Tuesday, the thought probably went through your mind. Maybe you shook it away, with every intention of giving yourself some time to reflect on the life and brilliance of the Say Hey Kid. But the thought kept coming back.

Who is the Greatest Living Ballplayer?

It’s Barry Bonds, right? It’s got to be Barry Bonds.

Believe it or not—and you might not believe it, considering how often I’ve talked about Barry Bonds’ brilliance and that I ranked him third in The Baseball 100—I actually have a different answer. A couple of them, even.

We’ll get to them in a minute.

First: Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start. The very first reference I can find to the phrase “Greatest Living Ballplayer” is in the Chicago Tribune in 1887. And the ballplayer the paper was referencing? Chicago Cubs third baseman Ned Williamson.

If you have heard of Williamson, it’s almost certainly because, in 1884, he hit 27 home runs, setting the record that would not be broken until 1919, when a pitcher and hitter named George Ruth hit 29. Williamson never hit more than nine home runs in any other year, so there’s a temptation to think that 1884 was a fluke. But it actually wasn’t. In 1883, he hit 49 doubles in 98 games. In 1883, a ball hit over the fence was counted as a ground rule double.

In any case, in 1887, the Tribune wrote that “by many, Williamson is considered the greatest living ball-player,” and this was because of his defense: “He is a great man in short field, eating balls which to ordinary men would figure as hit.”

Over the next, oh, 100 or so years, any number of players were referenced in passing as the “Greatest Living Ballplayer.” In 1903-04, there were several GLB references to Napoleon Lajoie. Then, it was Honus Wagner. Ty Cobb, around 1910, announced that he wanted to surpass Wagner and become the Greatest Living Ballplayer. and newspapers soon after began to refer to him that way.

Cobb more or less owned GLB until his death in 1961. It wasn’t a big deal, almost nobody mentioned it, but every now and again someone would write a Cobb story and call him the greatest living ballplayer, lower-case. Nobody seemed to argue, not even Babe Ruth fans.

From 1962 to 1969, the title was more or less vacated. In 1966, the Oakland Tribune did refer to Willie Mays as the GLB for the first time. But that, too, was a passing reference, and was never followed up.

And then, in 1969, everything changed with one vote. The Baseball Writers Association voted two teams—the Greatest All-Time Team and the Greatest Living Team. See if you can find the main point:

RHP: Walter Johnson (All-Time); Bob Feller (Living—died in 2010)

LHP: Lefty Grove (All-Time); Lefty Grove (Living—died in 1975)

C: Mickey Cochrane (All-Time); Bill Dickey (Living—died in 1993)

1B: George Sisler (All-Time); George Sisler and Stan Musial (Living)*

2B: Rogers Hornsby (All-Time); Charlie Gehringer (Living—died in 1993)

3B: Pie Traynor (All-Time); Pie Traynor (Living—died in 1972)**

SS: Honus Wagner (All-Time); Joe Cronin (Living—died in 1984)

LF: Ty Cobb (All-Time); Ted Williams (Living—died in 2002)

CF Joe DiMaggio (All-Time); Joe DiMaggio (Living—died in 1999)

RF: Babe Ruth (All-Time); Willie Mays (Living—died in 2024)

*Sisler died in 1993, Musial in 2013, and I’m not sure why they tied for the Living list but not for the All-Time list.

**It’s so puzzling to look back and see the esteem writers in the late 1960s still had for Pie Traynor. It’s less baffling when you realize that Traynor was a broadcaster, a wonderful storyteller and utterly beloved throughout baseball. Meanwhile, the guy this SHOULD have been, Eddie Mathews, was passionately disliked by many of the writers, including the cantankerous Dick Young, who was the center of gravity for the Baseball Writers Association in those days.

There’s a little bit to unpack here, particularly the fact that the writers put Willie Mays in rightfield to get him on the living team, which, you know, on the one hand, I get it, because having an all-time living baseball team without Willie Mays would have been ridiculous. On the other hand, listing Willie Mays as a rightfielder is like listing Leonardo Da Vinci as an auto mechanic. I’m sure he’d have been able to do one helluva tuneup, but it entirely misses the point.

But the point was simple: DiMaggio got more votes than Mays did. He was the only living position player to get enough votes to be put on both lists.

So, on the day the teams were announced, DiMaggio was called to the stage to accept three different awards:

All-time centerfielder

Greatest Living centerfielder

Yes, Greatest Living Ballplayer

“I damn near got a charley horse from those three long walks to get the awards,” Joltin’ Joe said gleefully—or, anyway, as gleefully as he ever got. “His eyes danced,” Arthur Daley reported for The New York Times.

Now, look, even in 1969, even though he would still play for four more years, Willie Mays was the greatest living ballplayer. But, and this is important as we go forward, Mays idolized DiMaggio. He actually walked around the awards ceremony that day asking people, “Where’s my idol? Where’s Joe D?”

“Ted Williams was the best hitter,” Mays told The New York Times. “But I picked Joe to pattern myself after because he was such a great all-around ballplayer.”

As the years went along, Joe DiMaggio turned “Greatest Living Ballplayer” into something more than a casual title. It became the way he was introduced at every single appearance he made. He insisted on it.

Card shows? “Greatest Living Ballplayer.”

Banquet? “Greatest Living Ballplayer.”

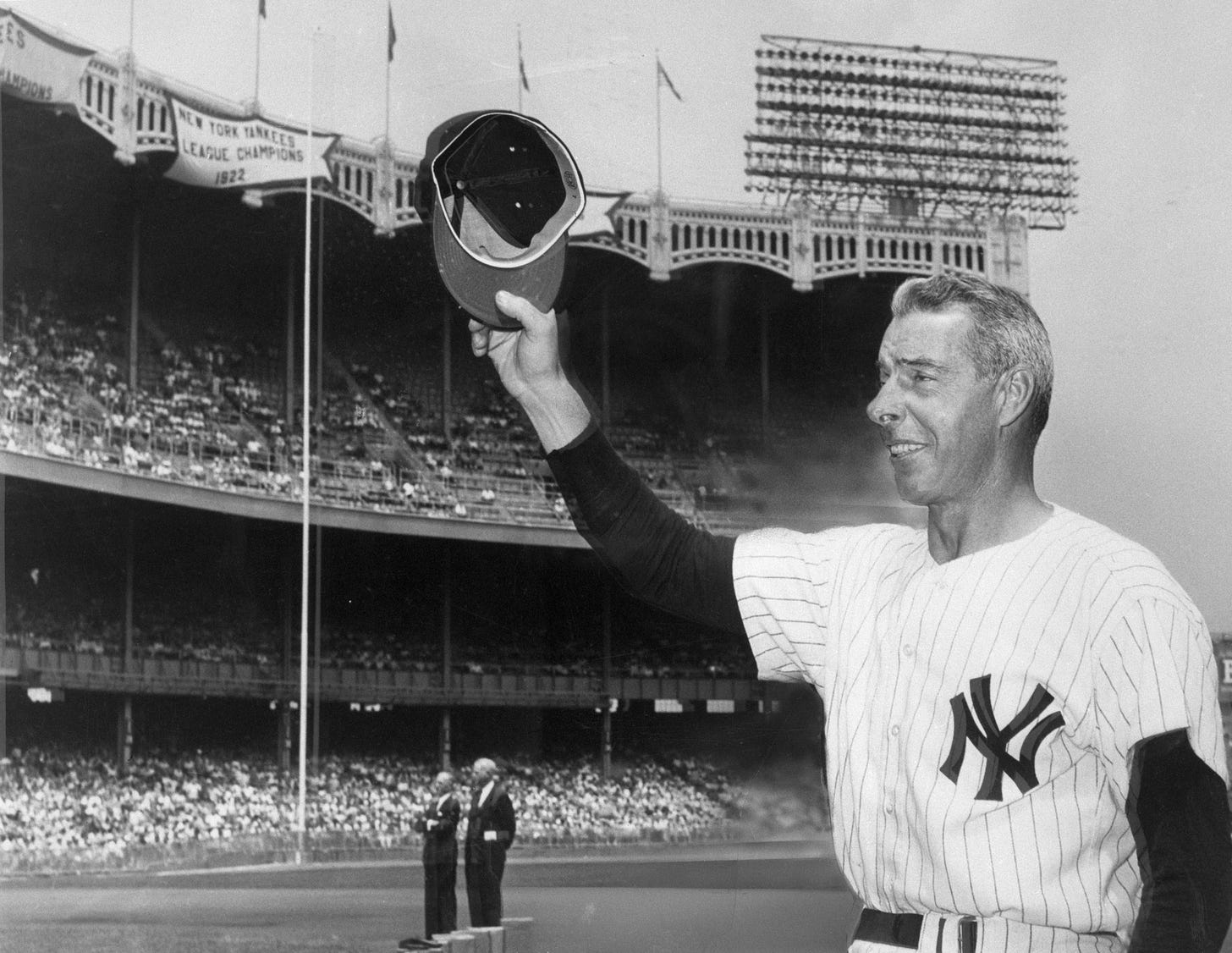

Walk on the field at Yankee Stadium? Obviously, there, Bob Sheppard would introduce him as “the Greatest Living Ballplayer,” among many other glowing epithets and sobriquets and appellations, and Joe D. would do the two-handed wave he had perfected, and the crowd would roar. There would be no protests for Mays or Musial or Williams at Yankee Stadium.

In truth, though, there really weren’t protests anywhere. For one thing, Dick Young wrote that DiMaggio was the greatest player he ever saw, and nobody really wanted to pick a fight with Dick Young. And, as the decades passed, and those words melded with Joe DiMaggio, I think “Greatest Living Ballplayer” came to represent something larger than baseball performance. It became an ideal.

Joe DiMaggio was a near-perfect ballplayer—“he could beat you five different ways” Casey Stengel said—but he was larger than that, larger than life. He stopped a nation with a 56-game hitting streak in that summer before America went to war. He lost three full prime seasons to World War II, leaving it to the imagination what his numbers might have looked like.* He married Marilyn Monroe. (“You never heard such cheering,” she said to him after returning from a USO Tour. “Yes I have,” Joe DiMaggio answered.) He was the hero the nation turned its lonely eyes toward.

He was Willie Mays’ idol.

So, yes, Greatest Living Ballplayer fit him in a way that it didn’t necessarily fit players who might have done more than him on the field.

*As our friend Jonathan Hock says, people will often talk about the years that Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams and Bob Feller and others lost to World War II, people seem to forget that Willie Mays lost most of his age-21 season and all of his age-22 season while serving in the military. When you consider that, upon his return in 1954, he hit .345/.411/.667 with 13 triples and 41 home runs, you have to at least ponder the possibility that he lost 55 home runs over the 275 or so games he missed. Those 55 home runs would have given him the all-time home run record before Henry Aaron broke it.

When DiMaggio died in 1999, Mays was pretty much the unanimous choice to take over that Greatest Living Ballplayer title. Mays was not as famous as DiMaggio—Simon and Garfunkel didn’t have a song about him—but he was famous enough. He was admired enough. He was beloved enough. Tony La Russa said that he likes to see a bunch of Hall of Famers together just to see which one of them inspires the most awe. Stan Musial inspired awe. Ted Williams inspired awe. Henry Aaron inspired awe. And yes, maybe most of all, Willie Mays inspired awe.

When Mays died, well, he was the last of the 1969 Greatest Living Players to go. In the last 25 years, we’ve lost Mays, Aaron, Musial, Williams, Frank Robinson, Morgan, Mathews, Kaline, Brooksie, Gwynn, Yogi, Banks, Snider and McCovey, among other legends. There are precious few fantastic ballplayers left from 50 or 60 years ago. In many ways, the passing of Willie Mays felt like the end of something.

But the end of one thing means the beginning of another.