What’s the deal with Mr. Met?

It’s funny, I’ve never once wondered about the background of other mascots. I’ve never thought twice about the Phillie Phanatic. I’ve never thought about what makes the San Diego Chicken tick, what motivates Youppi!, what gets KC Wolf up in the morning, what stuff Gritty is reading, what shows Tree is binge-watching, what Sparty does to stay in such great shape or if the Racing Sausages hang out after games.

But I think about Mr. Met all the time.

There’s a certain ennui that Mr. Met projects… and I don’t think it’s just from watching all those bad Mets games through the years. I’ve always sensed from Mr. Met a certain longing, a yearning to be something more than a baseball-headed mascot. But, alas, I admit that I may be projecting myself. Mr. Met has never sat down for an interview. The story goes that he lost his voice “root root rooting” for the Mets. But I believe the story to be a cover, a facade. I believe Mr. Met, like Bromden in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” can speak just fine, but he’s biding his time. He will speak when the moment is right.

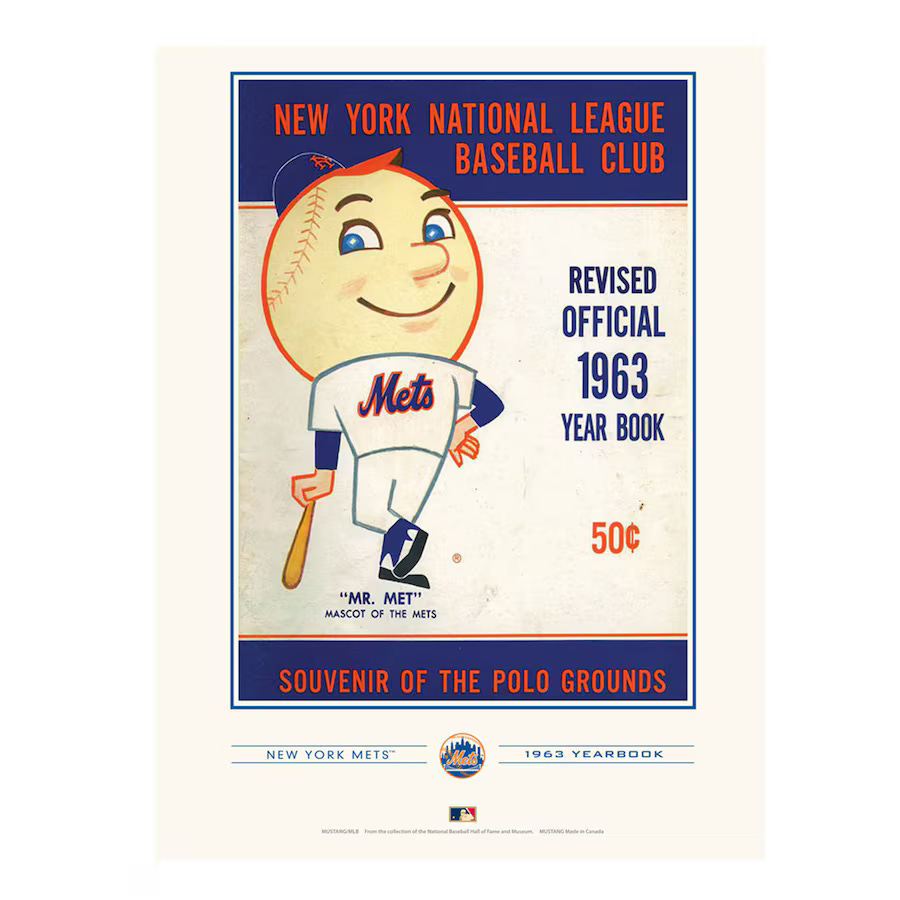

Mr. Met first made the cover of the New York Mets game program in 1963.

Paul Lukas, the man behind Uni Watch (and perhaps the only person more obsessed with Mr. Met than me), wrote a story more than 10 years ago for ESPN wherein he tried to track down who first drew Mr. Met—and he found that it was actually two artists, one named Charles Palminteri*, who worked for the Mad Men ad agency, and then another mystery artist who might very well have been comic book legend Al Avison, who created the Whizzer and also drew Captain America comics during the 1940s.

*Are all Palminteris named Charles? Although I just looked it up, I guess Chazz Palminteri is NOT named Charles, but rather Calogero. So, forget I brought it up.

Mr. Met made his first live appearance in 1964. It’s difficult to track down an exact date, but I’m betting on June 20, 1964, which was Ladies Day at Shea Stadium. We know from advertisements leading into the game that before the game, several Mets—including Ron Hunt (with his wife), Al Jackson and Tracy Stallard—were scheduled to appear at the Abraham & Straus Fourth Floor Restaurant to answer questions from women about the life of ballplayers.

“Mr. Met, the jolly team mascot, will be on hand too,” the ad promised, “with Mets pennants for everyone.”

By August, Mr. Met was famous enough that a huge line of kids formed to get his autograph at the World’s Fair. At one point during his autograph session, water from the Unisphere fountains splashed on him, leading one of the kids to shout: “Look! Mr. Met is all wet!”

Ah, this was just the first of the many indignities that Mr. Met has had to endure through the years.

Did people see him? Or did they just see his baseball-shaped head? He tried in his own ways to maintain dignity. He demanded that people call him Mr. Met; to this day, I have never heard anyone call him by his first name.